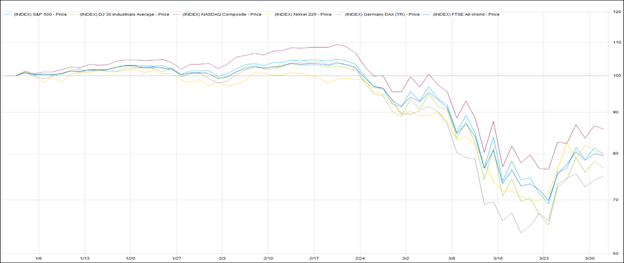

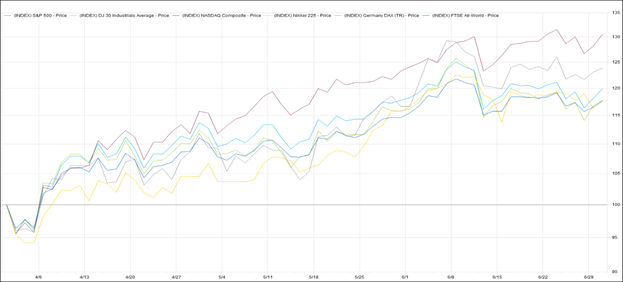

As COVID-19 continued to disrupt economic activity around the world for the majority of Q2, the forward-looking nature of financial markets was on full display as optimism largely pervaded and broad market indices posted remarkable gains. This performance should be taken in context, however, as Q1 ended shortly after markets bottomed amidst tumultuous trading. The following charts display the performance of select headline market indices Q1 (the same chart appeared in our previous letter) and Q2:

While both charts show obvious disparities among the performance of board market indices, the divergence in performance is perhaps best illustrated by juxtaposing the NASDAQ Composite, which returned 30.6% during the quarter, and the Dow Jones Industrial Index, which returned only 17.8% in Q2. We continue to observe unprecedented volatility and extreme pricing inefficiencies (relating to both overvalued and undervalued securities) and have been prudently capitalizing on opportunities to own the equity or debt securities of fundamentally sound business at attractive prices.

Anecdotally, many have observed that recently market volatility seems to be especially pronounced. The list of possible explanations is long, but one factor warrants specific mention: the “gamification” of investing. Last year, spurred by new market entrants such as Robinhood (a trading platform founded in 2013 available via mobile app and website), most major US retail brokerage platforms cut trading commissions to zero. To be sure, lowering barriers to participation in financial markets is a positive development. However, education around the risks and uncertainties of investing, especially in non-traditional financial instruments, may be lacking.

Among the more sobering tales of the pernicious consequences of the gamification of investing is that of Hertz Global Holdings, Inc. On May 22, the car rental company filed voluntary petitions for reorganization under Chapter 11 in the US Bankruptcy Court for the District of Delaware. In such proceedings, debt holders typically exchange their debt securities for equity securities in a reorganized entity, while equity holders find themselves holding worthless securities (and have their ownership interest cancelled by the Court). In early June, the judge handling the Hertz case consented to the sale of nearly 250 million new shares of stock – which would almost certainly be cancelled (and therefore rendered worthless) as part of the Hertz’s reorganization plan. In a Wall Street Journal article on this proposed stock issuance (a link to which is provided in the “From Our Library” section), Jared Ellias, a law professor at the University of California Hastings College of Law, was quoted as saying “Hertz looks at the market and sees there is a group of irrational traders who are buying the stock, and the response to that is to seek to sell stock to these people in hopes of raising some amounts of money to fund their restructuring.” While the proposed stock sale was ultimately scuttled when the SEC raised objections, this example highlights the perils of uninformed investing.

We work very hard to avoid situations such as this. Our judgement is not infallible, but we are often able to identify circumstances that may lead to the impairment of capital (which is our primary definition of investment risk). Charlie Munger once said of investing: “It’s not supposed to be easy. Anyone who finds it easy is stupid.” We agree with Mr. Munger that investing is not easy, nor is it meant to be a game. In the following sections, we discuss two measures – one quantitative and one qualitative – that factor into our investment analysis.

- Return on Invested Capital

In theory, an investment in a company’s equity securities has value only insofar as that company produces future cash flows per share with a discounted present value exceeding the current share price. The challenge we face is determining the value inferred by future unknown cash flows and comparing that value to the current price of the stock.

Many measurements are examined by financial analysts in pursuit of an answer to this age-old quandary. One such measurement is return on invested capital (ROIC) – the earnings generated by a business based on the amount of capital invested in the business’s operations. For such a straightforward definition, it is surprising how many variations of the calculation exist (although perhaps this is sensible considering the complexity of modern financial reporting). McKinsey & Company presents their preferred formula in their textbook on corporate valuation (aptly entitled Valuation), offering that “You might go so far as to say that this formula represents all there is to valuation. Everything else is mere detail.”

Internally, we continually consider the intricacies of ROIC calculations and how it fits into our larger framework of security analysis. These conversations are nuanced and sometimes defy simple answers; for example, when investing in the equity securities of a company, is it more appropriate to consider return on invested capital (which uses net operating profit after taxes as the numerator and both equity and debt capital as the denominator) or return on equity (which uses net income as the numerator and only equity capital as the denominator)?

Two of our recent equity investments – Donnelley Financial Solutions, Inc. and Heidrick & Struggles International, Inc. boast exceptional ROICs. While this is only a small part of our investment thesis, we believe it speaks to the quality of each company’s management, particularly their historical allocation of capital. We expect sound capital allocation patterns to continue, resulting in the creation of substantial shareholder value over time.

- The Role of the Board of Directors and the Purpose of a Corporation

In recent years, a decades-old debate has been reignited about the purpose of corporations and the role of a company’s board of directors. In August 2019, the Business Roundtable, a group of CEOs of major US companies, released a statement on the purpose of a corporation, affirming members’ “fundamental commitment to all of our stakeholders.” The statement was widely viewed as subordinating “stockholder primacy” in favor of a “stakeholder primacy.”

Put simply, stockholder primacy encompasses the idea that a corporation is run for the sole benefit of its owners (stockholders), whereas stakeholder primacy posits that a corporation should be run for the benefit of all stakeholders (the definition of a stakeholder can be broad and fluid), with the interests of each stakeholder group being considered appropriately.

In a May 2020 memo entitled “On the Purpose of the Corporation,” Martin Lipton, a founding partner of the law firm Wachtell, Lipton, Rosen & Katz (a firm which GVIC has opposed in previous activist undertakings), wrote: “We continue to advise corporations and their board that they may exercise their business judgement to manage for the benefit of all stakeholders over the long term.” Mr. Lipton is credited with creating the shareholder rights plan (often referred to as a “poison pill”) in 1982; such plans are designed to enable companies to thwart unwelcomed takeover bids (and typically frowned upon by informed shareholders). It comes as no surprise to us that a law firm with a rich history of obfuscating shareholders’ rights would make such a statement.

To be clear, in deference to the myriad political, environmental, social, and ethical dispositions of our clients (and employees), we carefully consider the non-economic merits of every investment added to client portfolios. Once we are comfortable with a corporation’s business undertakings, part of our qualitative due diligence focuses with the medium by which stockholders’ stake in a corporation is protected. This is the solely the role of – and the sole role of – a company’s board of directors.

The question of corporate purpose is nuanced. First and foremost, corporations require capital to fund startup costs, growth initiatives, and ongoing operations. It goes without saying that providers of this capital, who assume the risk of loss should the corporation fail (a risk that Hertz shareholders can appreciate), require compensation for assuming that risk – a return on investment. But successful corporations rely on several other constituencies: skilled and dedicated employees to operate the company, reliable vendors and suppliers to ensure continuity of supply chains, customers interested in purchasing the products produced or services offered by a company, and government and regulators to ensure an efficient economic and legal framework in which companies operate (to name but a few). Corporations are responsible to each of these constituents in a unique way, perhaps more out of necessity than charity; any company that fails to train and retain skilled employees, cannot secure reliable supply chains, does not produce products or offer services demanded by customers, or runs afoul of governments or regulators is almost certainly doomed to fail. Each stakeholder relies on the corporation to fulfill its responsibilities to every stakeholder in the course of fulfilling its responsibilities to all stakeholders. It is sensible and necessary for the purpose of a corporation to be so multifaceted.

The more interesting question involves the mechanisms that mediate the relationship between a corporation and its various stakeholders. A company’s relationships with its employees can be mediated by employment contracts, labor unions, laws, or simply the company’s interest in retaining employees with skills specific to discharging their job duties. Vendors and suppliers negotiate terms that are contractually enshrined. Customers’ relationships with a company are largely market-driven; that is, consumers have wants and needs, and companies must create products or offer services to meet those needs at reasonable prices. Governments and regulators create laws and rules that establish the boundaries of corporate operations. To be sure, none of the above stakeholders forego risk, but each also derives certain benefits specific to the stakeholder’s relationship with the company.

Similar mechanisms exist to mediate the relationship between a corporation and its capital providers, or investors. Broadly, capital is provided either as debt or equity financing. Debt financing, provided in the form of a loan, bond, or similar instrument, is governed by a loan agreement, bond indenture, or other document, which serves as a contractual agreement that specifies the rights and responsibilities of the debtor and the creditor. Violations are enforceable through the court system, and because of the comprehensive and straightforward nature of such contracts, there is little room for interpretation.

Equity financing, like debt financing, has a specific mechanism to mediate the relationship between providers of equity capital and a corporation: a board of directors. This is the sole mechanism to protect the interests of equity shareholders, and the sole responsibility of the board of directors is to protect the interests of equity investors. Because equity investors bear more risk than perhaps any other stakeholder (the complete impairment of invested capital should a corporation fail), they are compensated with an ownership interest in the corporation; that ownership interest defines, and is unique to, equity investment. The risk born by equity investors, represented by ownership in the corporation, entitles equity investors to the excess profits of the corporation. The role of the board of directors is only to protect the interests of this constituency. This is where we find Mr. Lipton’s assertion so objectionable: few will debate that a corporation’s purpose is to serve the interests of various stakeholders (or that to ensure survival, it must serve the interests of various stakeholders), but the idea that the board of directors is responsible to any stakeholder other than equity owners is preposterous.

The Council of Institutional Investors, which advocates for effective corporate governance practices and strong stockholder rights, was quick to respond to the Business Roundtable’s August 2019 statement, sternly retorting: “CII believes boards and managers need to sustain a focus on long-term shareholder value. To achieve long-term shareholder value, it is critical to respect stakeholders, but also to have clear accountability to company owners.” We could not agree more.

From Our Library

Our research and advisory team is currently reading The Outsiders by William N. Thorndike, Jr. The book profiles eight unconventional CEOs and their unique approaches to creating shareholder value, particularly as a result of capital allocation decisions. Although each takes a different approach, some common themes include opportunistic business acquisitions at inexpensive valuations and business sales at rich valuations, decentralized management structures, and stock repurchases.

One of the CEOs profiled by Thorndike is Bill Stiritz, who ran Ralston Purina from 1981 to 2000. Legendary value investor Michael Mauboussin offered the following quote to Thorndike in an interview about Stiritz: “Effective capital allocation… requires a certain temperament. To be successful you have to think like an investor, dispassionately and probabilistically, with a certain coolness. Siritz had that mindset.” We strive to invested in companies run by leaders like Bill Stiritz.

For those interested in additional reading on the subjects discussed above, we offer the following:

The Wall Street Journal on Hertz issuing up to $1 billion in new shares during bankruptcy proceedings: https://www.wsj.com/articles/bankrupt-hertz-wants-to-sell-up-to-1-billion-in-new-shares-11591917121.

Forbes on return on invested capital: https://www.forbes.com/sites/greatspeculations/2018/09/12/ceos-that-focus-on-roic-outperform/#5b1741aa567b.

A thoughtful essay by David Berger, a partner at the law firm Wilson Sonsini Goodrich & Rosati (which has and continues to represent our firm in a number of matters), on stockholder primacy entitled “Reconsidering Stockholder Primacy in an Era of Corporate Purpose” (via online repository SSRN): https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3327647. Alternatively, the essay is summarized by the Harvard Law School Forum on Corporate Governance: https://corpgov.law.harvard.edu/2019/03/04/reconsidering-stockholder-primacy-in-an-era-of-corporate-purpose/.

Firm Update

In mid-June, we welcomed Kevin Sanford as GVIC’s newest team member. Kevin was most recently Director of Sales & Business Development for a major New York credit institution, and has deep experience within and knowledge of technology, financial services, and fintech sectors. Kevin began his finance career at Bear Stearns and JP Morgan Chase in New York. Outside of work Kevin, and his wife Megan are active in their community. Kevin volunteers with a college access and success program serving underprivileged students and families in greater Newark, NJ.

We are currently in the process of transitioning between internal portfolio management applications. This is the result of years of passive searching for a solution that will enable our clients to have improved access to account information and streamline our internal processes. There will be no interruption to your existing account access, our accessibility, or the ongoing management of your accounts. We are excited to introduce access to a new client portal, which will be available online and through a mobile app, in the coming months.

Concluding Thoughts

We recognize that market volatility and geopolitical uncertainty, both of which are on full display, can cause consternation. However, the securities in which we have invested our clients’ capital possess sound fundamental financial characteristics that we expect will result in excellent investment returns over time. We invest as busines owners who are interested in the long-term viability and success of our portfolio companies, which requires good management making thoughtful capital allocation decisions, a focused board of directors to protect the interests of the equity owners of the business, and general corporate health encompassing the interests of each of a corporation’s stakeholders. We are steadfast in our investment discipline and will only invest when our criteria are met. We adhere to this discipline, through thick and thin, in the pursuit of superior investment returns. Thank you for the trust and confidence you place in us as stewards of your investment capital.

Your Investment Research and Advisory Team

Global Value Investment Corp.